Introduction

Digital language death is a real issue for many small and under-resourced languages. To use Kornai’s (2013) terms, the digital moribund state of languages is accelerated by the lack of intuitive and useful text input methods for many minority and under-resourced languages. Even if text input methods currently exist for a language, it is often the case that they are disruptive (rather than smooth) to the digital text production process, due to inadequately optimized keyboards. This disruption then serves as a barrier to creating vibrant digital communities using these under-resourced languages. What is observed is that users of under-resourced languages often choose to use another language in digital contexts rather than deal with the disruptions of awkward keyboard input requirements. This actually serves to accelerate and solidify the under-resourced language in its moribund “vitality” state. Optimized Keyboard Layouts are an academic pursuit in applied mathematics and computer science which intend to make keyboards intuitive and useful. Despite being language-related resources, keyboards and text input methods are rarely mentioned in the language development literature. Within the computer science literature Yin and Su (2011) situate the optimization of the keyboard in a context known as the general keyboard arrangement problem (GKAP). Their work is well respected, but does not take into account several issues common to the minority-language context, such as keyboards with deadkey interactions, graphemic complexities (such as diacritic usage), and embedded linguistic knowledge (such as tone patterns, or multi-graph functional units). For example, Bi et al. (2012) look at the efficiency of text input with the deadkey method for diacritics, and contrast that with a single keystroke for a “composed” character. They conclude that the deadkey method is more efficient, but they only run their tests on European languages with orthographies that have a diacritic to total character density of less than 4%. Commonly, European languages use diacritics to indicate vowel quality. In contrast, many languages use diacritics to show tone patterns. In preliminary counts of minority-languages in both Mexico and Nigeria, I have encountered diacritic densities of over 30%. This means the extra time and effort it takes to use deadkeys is much more significant in these languages. Paterson (2014) lays a foundation for the kinds of issues encountered by minority-languages typists, as an appeal to creators of resources for under-resourced languages to use design principles (Vitsœ 2012, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2018) in the creation of their language resource products. There, I argue that better design of text input solutions, which take into account linguistic knowledge about a language’s orthography, will increase the opportunities for digital vitality in an under-resourced language. It does not, however, present a methodology for assessing the disruptive nature of a text input solution, so we still lack a metric for comparing the relative ease of typing on any given keyboard layout for a given language. There currently does not exist a principled way to evaluate the utility or the application of User Experience principles (Garrett 2002) and design criteria to keyboard layouts. Researchers who have published on the keyboard optimization problem generally evaluate keyboard layouts on the basis of a composite “fitness score”. These scores only take into account the metrics of a single language - generally English - and only do it from an ergonomic perspective. As researchers in the field of language development, we are effectively blind when it comes to our ability to compare efficiency of two proposed keyboard layouts serving the same language,. A good framework does not exist for allowing researchers to ask the question: does QWERTY serve English users equally as well as AWERZY does to French users? - or any number of keyboards and their corresponding minority-languages. Language development practitioners and linguists working in many different languages have created many keyboard layouts. However, linguists have not adequately accounted for the linguistic dissonance between the psycholinguistic and phonemic realities of a spoken language and a speaker’s experience in typing that language. This has created a gap between the “possible to write/type” orthography and the “easy to write/type” orthography. The general keyboard arrangement problem (GKAP) has been situated as a time over distance problem, i.e., speed. The assumption has been that if fingers travel a smaller distance, then faster typing should be the result. A secondary argument to increase speed has been to reduce effort. The assessment of effort has been tied to Fitts’ law (MacKenzie 1992) for measurements of physical effort. However, mental effort or user-perceived effort remains unassessed. By visualizing keystrokes, we can identify the locus of impact in any given language. In language development work it is often the case that low-usage keys in an English-QWERTY layout are replaced with “new characters” to form keyboard layouts. The consequence has been the placement of frequently used keys under weak fingers, as demonstrated by the Meꞌphaa keyboard layout below. Notice the high frequency red(dish) areas and the lower frequency blue areas. These red areas would normally be struck with the pinky fingers.

Figure 1: Meꞌphaa Keyboard

Spanish, distributes the same amount of information across multiple fingers as shown in Figure 2 below. According to current keyboard layout theory even the Spanish keyboard is heavy on the weaker fingers of the left hand, but at least is better than the Meꞌphaa layout.

Figure 2: Spanish Keyboard

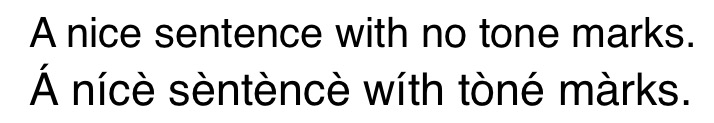

Contrasting these two languages allows us to visualize how they are different with respect to the actions of the pinky finger. It also demonstrates how the attempt to ‘conserve QWERTY’ impacts typing in minority languages. Notice how the Meꞌphaa keyboard layout replaces the Spanish〈ç〉character with a tone diacritic key. Also note that these tone diacritics are very frequent in Meꞌphaa, and create a typing imbalance. Additionally, the Meꞌphaa Saltillo〈ꞌ〉 key is also on the right side with heavy use, further contributing to the typing imbalance. These diagrams demonstrate the part of the keyboard layout analysis that can be computed using existing GKAP methods. What linguists bring to the discussion is an awareness of linguistic components. Orthographies are not just Unicode characters, but are functional units. The encoding of a functional unit can change from orthography to orthography. This is missed by many GKAP researchers. One needs to look beyond Unicode characters and toward ratios of keystrokes to functional units. One way that linguists look at functional units differently than “pure technologists” is in the area of tone. Snider (2014) and Hyman (2014) both argue for an analysis of tone that looks at patterns across the domain of tonal attachment (usually the word or morpheme) rather than the more structuralist and segmental view of “letter plus pitch” which is the encoding method that Unicode follows. The difference in behavior becomes clearer when we contrast reading diacritic tone marks with a language which does not use diacritical marking. Imagine the following example represents the same sentence in two different languages.

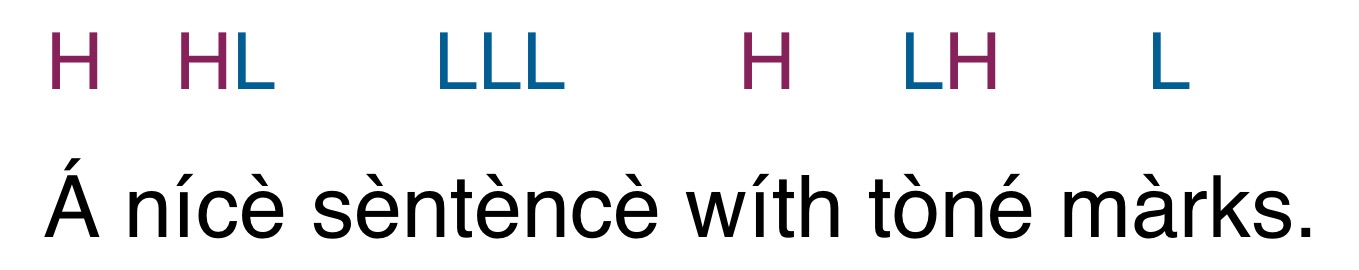

A tone pattern analysis (following Snider and Hyman) would suggest that we should understand the tonally marked sentence to represent the segmental and the suprasegmental tiers separately, something like the following:

It is observed, anecdotally, that many writers of tone languages parse the writing task into two activities, one for each tier of information. Usually the segmental tier is completed first and then the suprasegmental tier.

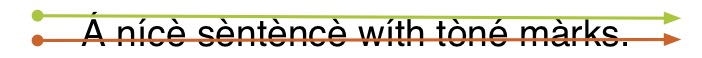

This makes the writing activity much like handwriting in the United States where we say: “don’t forget to dot your ‘i’s and cross your ‘t’s. The writer first completes the segmental tier and then comes back across with a second pass and completes dots the ‘i’s and crosses the ‘t’s. However, the nature of typing, and Unicode’s structural nature, requires typists to complete the text production task linearly by codepoint. This creates dissonance from what many language users find “natural”, requiring them to frequently alternate their attention between the two tiers, as shown by the up and down movement in the following diagram.

The goal of this thesis will be to develop and apply metrics to keyboard layouts so that their ease of use can be analysed and compared. Some optimised keyboards in a few sample languages will also be presented. Preliminary testing of these ideas has been done on English [eng], Spanish [spa], Me’phaa [tcf], and Chinantec [cso], as mentioned in Paterson (2014) and work done with Nigerian languages in Paterson (2015) covering Ezza [eza], Bekwarra [bkv], Cishingini [asg], Okphela [atg], and Igbo [ibo]. However, for this thesis I anticipate focusing on the three following languages: Navajo [nav], Kabiyè [kbp], and Eastern Dan [dnj], and especially the latter two, as they are related languages with very different design decisions in their orthographies, and both have very clear analysis of their tonal systems. This should allow observations about the typing process in one language to be contrasted with another related language. Further, there is a reasonable amount of text to work with in each language. Ultimately the final languages used will depend on the accessibility of corpora content in those languages.

This thesis will add to the current GKAP discussion by proposing a theoretical framework and a two-metric algorithm that can be applied to any keyboard layout for any language using a Latin based script. The first metric will account for disruption in the phoneme (or functional unit) stream while engaged in typing, and the second will account for non-character-producing keystrokes, thus addressing the major problem areas outlined above. These metrics will then be combined with a haptic fitness score to produce a fitness score which accounts for linguistic knowledge. This thesis will contribute to the ongoing language development discussion by providing a quality assessment metric for the evaluation of a very important language-based digital product.

Research questions

The problem to be addressed can be expressed informally like this:

“We have these keyboards layouts in all these languages, but they are not being used, and in general people find it easier to type in languages other than their mother tongue. To what extent are our keyboards disruptive and thereby impeding language use in digital contexts? Can we measure the disruption?”

More precisely, the following sub-questions can be addressed in the course of this investigation:

What percentage of extra work is required to type minority-language texts?

Here, the “extra work” measurement might be measured in terms of the distance traveled, the time required to travel that distance, and the number of keystrokes, as compared between a language of wider communication and a minority language.

In a given language, what is the added unnecessary distance when typing text?

What are some common traits of excessive use/difficulty in text input keyboards for minority languages, and how can those commonalities of “pain”, be generalized for designers to avoid?

Do we account for functional units (e.g. phonemes and tones) independent from character optimization? That is, does optimizing for character input also optimize for functional unit input?

Can we predict that with tone languages we will exceed the Hick’s law minimum, whereas in non-tonal languages we can stay under Hick’s law?

Hick’s law (Hick 1952) is a reference to how performance decreases as temporary memory functions increase, i.e., when we need to hold information in our temporary memory. This can be calculated on the basis of how many characters does one need to type in between the elements of a diacritic digraph.

How can we measure the dissonance factor for a particular keyboard layout? That is, how much dissonance does a keyboard layout solution induce?

Dissonance is the cognitively difficult, or non-prefered choices that we must make to achieve the desired results. Dissonance is increased by those things which militate against fluidity, and includes factors such as non-correspondence between keystrokes and functional units, the elements of a digraph, and multiple keystrokes per orthographic character.

Project specifics

To perform the supporting analysis I will use existing texts to form a “corpus of keystrokes” and a “corpus of functional units”. I use the corpus of texts in conjunction with the existing keyboard layout to suggest what the “keystrokes required” would have been to produce a text (assuming 100% accuracy). Given that I am working with corpora, rather than original production data, I will not have actual time-over-distance measurements. I will rather, as is the norm for working with corpora in this context, infer the time to completion for each keystroke based on previously published experiments which show the time it takes to move a finger from one key to another. Then I will look at the functional units and measure (1) how many keystrokes to functional units are required, and (2) how much dissonance is created in the process of typing. Existing keyboard layouts for the languages of the texts in question will be analysed, and scored. Finally, improved keyboard layouts with better scores will be suggested.

References

- Xi Bi, BA Smith, S Zhai (2012) Multilingual touchscreen keyboard design and optimization. Human–Computer Interaction 27(4), 352-382.

- Garrett, Jesse James (2002) The Elements of User Experience: User-Centered Design for the Web. New Riders Publishing, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

- Hick, W. E. (1952) On the rate of gain of information. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 4 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1080/17470215208416600

- Hyman, Larry M. (2014) How To Study a Tone Language, with exemplification from Oku (Grassfields Bantu, Cameroon). Language Documentation & Conservation 8.525-62.

- Kornai, A. (2013) Digital Language Death. PLOS ONE 8(10): e77056. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077056

- MacKenzie, I. Scott. (1992) Fitts’ law as a research and design tool in human-computer interaction. Human-Computer Interaction 7, 91-139.

- Paterson, Hugh J., III (2014) Keyboard layouts: Lessons from the Meꞌphaa and Sochiapam Chinantec designs. In Jones, Mari C. (ed.), Endangered Languages and New Technologies, 49-66. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Paterson, Hugh J., III (2015) African languages: Assessing the text input difficulty. Presentation at the 46th Annual Conference on African Linguistics, Eugene Oregon.

- Peng-Yeng Yin, En-Ping Su (2011) Cyber Swarm optimization for general keyboard arrangement problem., International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 41(1), 43-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2010.11.007.

- Snider, Keith L. (2014) On Establishing Underlying Tonal Contrast. Language Documentation & Conservation 8.707-37. http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/24622

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2018) Interaction Design Basics. <Accessed 2 March 2018>. https://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/interaction-design.html

- Vitsœ (2012) Dieter Rams: ten principles for good design. <Accessed 27 June 2012>. http://www.vitsoe.com/en/gb/about/dieterrams/gooddesign

Categories: