Dublin Core DCMIType: PhysicalObject

I have been working through the DCMIType vocabulary. I have been applying it to models and situations relevant to language and culture research. I have specifically been working with data from the Open Language Archive Community (OLAC). For example, their OAI-PMH aggregation data. However, I have also been interested in expanding the OLAC community of contributors and considering how the context of stakeholders in the OLAC community could be described more fully in the OLAC aggregator. In this post I am contemplating the DCMIType PhysicalObject.

By way of background, (Citation: Paterson III, 2022) Paterson III, H. (2022). An OLAC Perspective on Services: The Forgotten Language Resources. Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. Retrieved from https://hughandbecky.us/Hugh-CV/talk/2022-services-the-forgotten-language-resources/DC_2022_Conference_Paper_Paterson_Revisions_pre-print.pdf indicates that the OLAC aggregator only has four instances of the use of the DCMIType PhysicalObject while (Citation: Paterson III, 2022) Paterson III, H. (2022). Where Have All the Collections Gone?: Analysis of OLAC Data Contributors’ use of DCMIType ‘Collection’. Society of American Archivists. Retrieved from https://www2.archivists.org/am2021/research-forum-2021/agenda#peer indicates that only eighty-three percent of the 449, 498 OLAC records use the DCMIType vocabulary.

The DCMIType PhysicalObject is currently defined in the following way by the DCMI:

Definition version 003: An inanimate, three-dimensional object or substance.

Comment: Note that digital representations of, or surrogates for, these objects should use Image, Text or one of the other types.

However, previously proposed definitions (Citation: Guenther, 1999) Guenther, R. (1999). Dublin Core Resource Types list. Library of Congress. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/marc/dc/typelist-19991118.html include:

Proposal version 1999: a non-human object or substance. This category includes objects that do not fit into any of the other categories on this list. In addition these objects must be approached physically to make use of them. For example - a computer, the great pyramid, a sculpture, wheat. Note that digital representations of, or surrogates for, these things should use image, text or one of the other types.

One advantage of the 1999 proposal version over the current version is that it makes the application of the type value clearer. For example, in (Citation: Paterson III, 2022) Paterson III, H. (2022). DCMIType PhysicalObject. Retrieved from https://github.com/dcmi/usage/issues/117 I asked the following:

I am wondering can I get some clarity on the use of DCMIType

physicalObject. For example, when is the Rosetta Stone aPhysicalObjectand when is itText? The more common use case might be when is a cassette tape aPhysicalObjectand when is itSound? Clearly a basket in a museum is aPhysicalObject.

The answer for this question is clear in the older text but not in the current text. The Rosetta Stone should be classified as DCMIType text with a carrier or medium of stone.

Previously approved definitions in the vocabulary’s history have included the following:

Definition version 001: An inanimate, three-dimensional object or substance. For example – a computer, the great pyramid, a sculpture. Note that digital representations of, or surrogates for, these things should use Image, Text or one of the other types.

Given the low rate of use in the OLAC aggregator one might ask, how is this DCMIType even relevant? Ultimately it depends on the metadata model employed in the description of language research and language documentation activities. OLAC metadata is based on Dublin Core (Citation: Bird et al., 2004) Bird, S. & Simons, G. (2004). Building an Open Language Archives Community on the DC Foundation. In Hillmann, D. & Westbrooks, E. (Eds.), Metadata in practice.. American Library Association. , and Dublin Core includes the DCMIType vocabulary. It follows then that since it is included that it might be useful to explore in which ways it can be utilized within the OLAC space. Additionally, because Dublin Core is used by more than just OLAC any discussion or conceptualization within the Dublin Core framework might be useful for larger audiences. Therefore, I have been reading the literature and note two different, but interesting, use cases which seem to relate to DCMIType PhysicalObject. In addition I think, I can find several examples for uses within language archives.

Literature Based Use Cases

In reviewing literature, I have found two interesting use cases which relate to physical objects. These include places and pants. The DCMIType vocabulary specifically excludes humans. I guess humans were not considered a viable catalog-able entity. This can present challenges when indexing human remains. For example, Egyptian mummies are a less-controversial case of human remains which ought to be cataloged and may be relevant to the study of specific ethnolinguistic communities. However, other more-controversial cases also exists such as the remains of indigenous Americans (Citation: Ousley et al., 2005) Ousley, S., Billeck, W. & Hollinger, R. (2005). Federal Repatriation Legislation and the Role of Physical Anthropology in Repatriation. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 128(S41). 2–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20354 and indigenous Australians (Citation: Watson, 2003) Watson, N. (2003). The Repatriation of Indigenous Remains in the United States of America and Australia: A Comparative Analysis. Australian Indigenous Law Reporter, 8(1). 33–44. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26479533 within archives and museums in the United States (Citation: Thomas, 2015) Thomas, M. (2015). Bones as a Bridge between Worlds: Responding with Ceremony to the Repatriation of Aboriginal Human Remains from the United States to Australia. In Darian-Smith, K. & Edmonds, P. (Eds.), Conciliation on colonial frontiers: conflict, performance, and commemoration in Australia and the Pacific Rim.. Routledge. . The DCMIType vocabulary, by excluding a category for humans, forces institutions to forgo one of the following: the standard, the element, or the vocabulary. Alternately, this forces an analysis that human remains are physical objects and no-longer human. Many languages consider state changes worthy of distinct vocabulary. For example, a caterpillar and a butterfly are the same living creature, but the state is different.

A similar situation arises with DNA samples or specimens. Are these specimens still human, or are they physical objects in the DCMIType inanimate sense? The appropriate way to conceive of DNA is a question many researchers face (Citation: Alpaslan-Roodenberg et al., 2021) Alpaslan-Roodenberg, S., Anthony, D., Babiker, H., Bánffy, E., Booth, T., Capone, P., Deshpande-Mukherjee, A., Eisenmann, S., Fehren-Schmitz, L., Frachetti, M., Fujita, R., Frieman, C., Fu, Q., Gibbon, V., Haak, W., Hajdinjak, M., Hofmann, K., Holguin, B., Inomata, T., Kanzawa-Kiriyama, H., Keegan, W., Kelso, J., Krause, J., Kumaresan, G., Kusimba, C., Kusimba, S., Lalueza-Fox, C., Llamas, B., MacEachern, S., Mallick, S., Matsumura, H., Morales-Arce, A., Matuzeviciute, G., Mushrif-Tripathy, V., Nakatsuka, N., Nores, R., Ogola, C., Okumura, M., Patterson, N., Pinhasi, R., Prasad, S., Prendergast, M., Punzo, J., Reich, D., Sawafuji, R., Sawchuk, E., Schiffels, S., Sedig, J., Shnaider, S., Sirak, K., Skoglund, P., Slon, V., Snow, M., Soressi, M., Spriggs, M., Stockhammer, P., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Thangaraj, K., Tiesler, V., Tobler, R., Wang, C., Warinner, C., Yasawardene, S. & Zahir, M. (2021). Ethics of DNA research on human remains: five globally applicable guidelines. Nature, 599(7883). 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04008-x . Presumably after analysis they could be DCMIType Dataset. Again, the vocabulary requires a view or perspective to be take on artifacts and their records. These views may not be shared by all stakeholders.

Agriculture

Within the domain of Agriculture, plants may be the cataloged object. This is in part what motivates Cox’s question to the DCMI board as they are looking at the development and refinement of Darwin Core (Citation: Cox, 2021) Cox, S. (2021). Why is dctype:PhysicalObject ‘inanimate’?. Retrieved from https://github.com/dcmi/usage/issues/101 . The definitions above pivot on the exclusion of the animate—in favor of the inanimate. Depending on one’s view of the world, the animate/inanimate division may split differently. The following are some possibilities.

| Animate | Inanimate |

|---|---|

| Human | Non-human (Animal/Plant/Other) |

| Human/Animal | Plant/Other |

| Human/Animal/Plant | Other |

The DCMIType definition is not super clear on where the line is drawn cross-linguistically. Logically, for biologists the inanimate often excludes the living—such as plants and animals. This is one of the driving motivations in the of development Darwin Core (Citation: Endresen et al., 2012) Endresen, D. & Knüpffer, H. (2012). The Darwin Core Extension for Genebanks Opens up New Opportunities for Sharing Genebank Datasets. Biodiversity Informatics, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.17161/bi.v8i1.4095 (Citation: Baskauf et al., 2016) Baskauf, S. & Webb, C. (2016). Darwin-SW: Darwin Core-based terms for expressing biodiversity data as RDF. Semantic Web, 7(6). 629–643. https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-150203 (Citation: Baskauf et al., 2016) Baskauf, S., Wieczorek, J., Deck, J. & Webb, C. (2016). Lessons learned from adapting the Darwin Core vocabulary standard for use in RDF. In Hitzler, P. & Janowicz, K. (Eds.), Semantic Web, 7(6). 617–627. https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-150199 and its class Organism.

Places

As mentioned in the text of the DCMIType definition version 001, buildings are permissible referencial entities of the DCMIType PhysicalObject. The great pyramid is mentioned. Otherwise place as a catalog-able genre/type is absent. There is no way to indicate the is-ness as being a location. The absence of a value of “place” in the DCMIType vocabulary is noted (perhaps whishfully) by (Citation: Ostermaier et al., 2008) Ostermaier, B. & Bolliger, P. (2008). Creating Location-Based Services by Utilising a Web of Places. IEEE Computer Society. https://doi.org/10.1109/SAINT.2008.49 where they say: “Note that there is currently no such type defined [as place] in DCMIType, however, we expect this to change in the future.”

However, some “places” such as buildings are physical objects and have a spatial coverage1. So while place is not a valid DCMIType or generally a catalog-able entity, buildings are. This is certainly in the domain of intended usage for the DCMIType PhysicalObject.

Language and Culture Based Use Cases

With the previously mentioned uses, it is clear that linking cataloged objects from the domains of biology, anthropology, and archeology can be important to OLAC and end-users to the OLAC aggregator. These resources can be aggregated within OLAC if they are described with records via Qualified Dublin Core and fed via an OAI feed to OLAC.

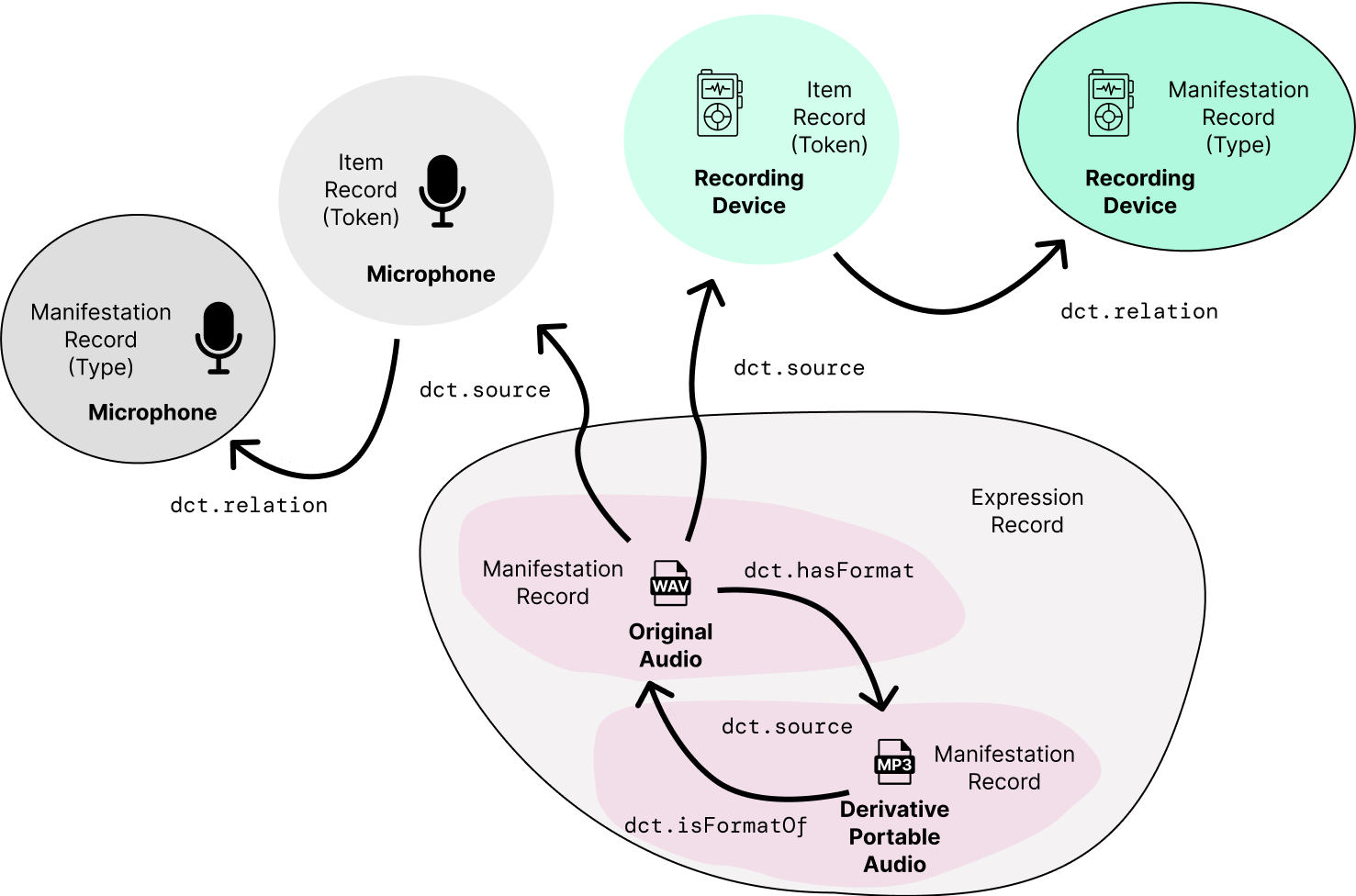

However, there are some use cases within the OLAC community of documentation and research related to languages which could demonstrate the use of the DCMIType PhysicalObject. Two cases come to mind: microphones and recording devices.

Both of these devices may be used for orginal sound and video capture/creation but may also be used in the digitization process.

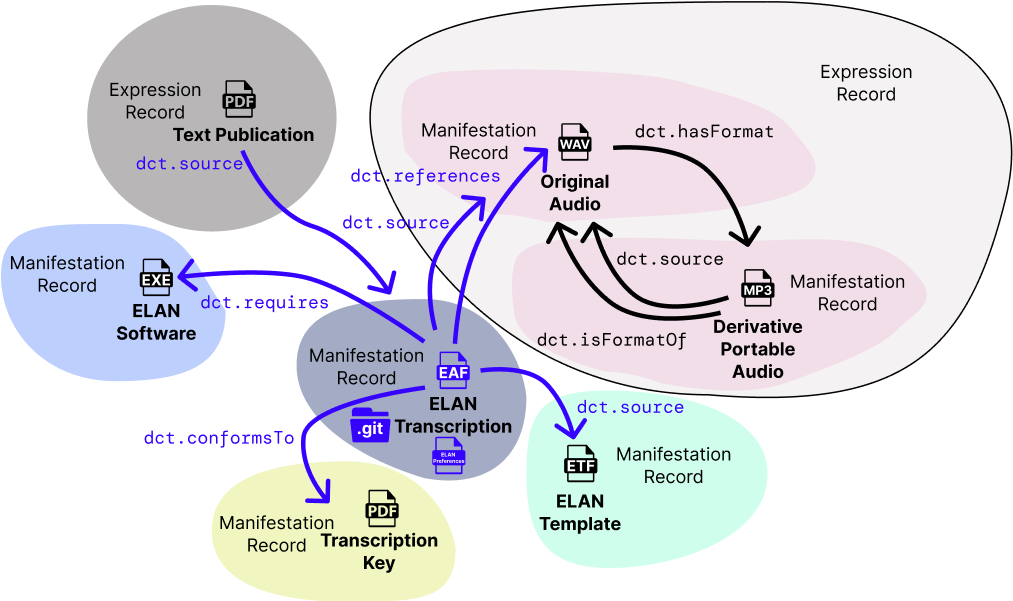

To illustrate how these objects could be used in the OLAC metadata context, I present three things. First, I illustrate their description model. I have previously written about describing audio annotations, and in that work I presented the following visual diagram.

Audio transcriptions illustrated with their Dublin Core relationships. Credit: Hugh Paterson III

Now this diagram can be extended to include the physical objects used to create the primary orginal audio file.

Microphones and recorders illustrated with their Dublin Core relationships.

Credit: Hugh Paterson III

The relationship between the manifestation record and the record for the physical objects can be expressed through the Dublin Core element Source which is a special type of relationship.

Dublin Core Definition: Source

Dublin Core Definition: A reference to a resource from which the present resource is derived.

Dublin Core Comment: The present resource may be derived from the source resource in whole or in part.

Second, as shown in the following table, the potentially applicable metadata elments from Dublin Core are explored.

| Microphone Example | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dublin Core Element | Value | Usage Explaination |

| title | Røde M3 | What is the advertised label? |

| type | PhysicalObject | DCMIType |

| description | The description should include: Voltage, Connection, Pickup Pattern, Specifications | |

| abstract | The M3 highly versatile end-address condenser microphone is designed to excel in a wide variety of recording situations in the studio, on stage or on location. Featuring an internally shock-mounted 1/2-inch condenser capsule, the M3 can either be powered by P48 phantom power or an internal 9V battery. It offers the versatility of a selectable pad (-10dB, -20dB) and high-pass filter (80Hz), making it ideal for recording everything from electric guitar to vocals to drums. | A summary of the object. For microphones should include: Voltage, Connection, Pickup Pattern, Specifications |

| accrualMethod | Purchase | What was the method by which this resource was acquired? Consider if any of the accrual methods in the Accrual Method Vocabulary |

| provenance | Purchased new from B & H Photo in 2010. | "A statement of any changes in ownership and custody of the resource since its creation that are significant for its authenticity, integrity, and interpretation." Statements of use need not be included if they are inferable from records. For example, I used this mic in Mexico and Nigeria but if I have recordings connected to this mic then those use instances are inferable. |

| identifier | Paterson #069 | Local inventory number |

| identifier | S/N 0027437 | Item level serial number; usually the model number is in the title. |

| date | 2010 | Date of acquisition or a general date if other more specific dates are not used. |

| available | 2001-10-02 | Date the product came on the market |

| created | Date of Manufacture or Creation | |

| replaces | A link to the item this item replaced. | |

| requires | Phantom Power (9 volt battery or 48 volt) | What dependencies does this object have for its utility to be acuated? Each requirement should be in its own element. |

| requires | XLR cable | What dependencies does this object have for its utility to be acuated? |

| issued | Date of formal issuance of the resource. | |

| conformsTo | An established standard to which the described resource conforms. | |

| rightsHolder | Hugh Paterson III | The entity for which the rights statement applies. |

| rights | Owner | On an microphone, "ownership" is the most appropriate rights statement in this context. |

| relation | Link to General record for all Røde M3 microphones. | This is a Token Record (WEMI: Item) and should be linked to a WEMI: Manifestation record a.k.a Type Record |

Third, I have included the following OLAC record in XML to show how it might be encoded.

<olac:olac>

<dcterms:title xml:lang="en">Røde M3</dcterms:title>

<dcterms:identifier>Item</dcterms:identifier>

<dcterms:identifier>Paterson #069</dcterms:identifier>

<dcterms:identifier>S/N 0027437</dcterms:identifier>

<dcterms:identifier xsi:type="dcterms:URI">https://rode.com/en-us/microphones/live/m3</dcterms:identifier>

<dcterms:type xsi:type="dcmitype:DCMIType">physicalObject</dcterms:type>

<dcterms:provenance>Purchased new from B & H Photo in 2010.</dcterms:provenance>

<dcterms:date xsi:type="dcterms:W3CDTF">2010</dcterms:date>

<dcterms:rightsHolder>Hugh Paterson III</dcterms:rightsHolder>

<dcterms:rights>Ownership</dcterms:rights>

<dcterms:requires>XLR Cable</dcterms:requires>

<dcterms:requires>Phantom Power (9 volt battery or 48 volt)</dcterms:requires>

<dcterms:abstract>The M3 highly versatile end-address condenser microphone is designed to excel in a wide variety of recording situations in the studio, on stage or on location. Featuring an internally shock-mounted 1/2-inch condenser capsule, the M3 can either be powered by P48 phantom power or an internal 9V battery. It offers the versatility of a selectable pad (-10dB, -20dB) and high-pass filter (80Hz), making it ideal for recording everything from electric guitar to vocals to drums.</dcterms:abstract>

<dcterms:accrualMethod>Purchase</dcterms:accrualMethod>

<dcterms:available xsi:type="dcterms:W3CDTF">2001-10-02</dcterms:available>

</olac:olac>

Several of the items in the following may fit into a format element.

| Acoustic Principle | Pressure gradient |

|---|---|

| Active Electronics | JFET impedance converter with bipolar output buffer |

| Capsule | 0.50” |

| Address Type | End |

| Frequency Range | 40Hz - 20kHz (selectable high-pass filter @ 80Hz) |

| Output Impedance | 200Ω |

| Maximum SPL | 142dB SPL |

| Maximum Output Level | 9.2mV (@ 1kHz, 1% THD into 1KΩ load) |

| Sensitivity | -40.0dB re 1 Volt/Pascal (6.30mV @ 94 dB SPL) +/- 2 dB @ 1kHz |

| Equivalent Noise Level (A-Weighted) | 21dBA |

| Output Connection | XLR |

| Power Requirements | 9V battery, P24 or P48 |

| Mechanical Specifications | |

| Dimensions (mm) | Height: 225 |

| Width: 33 | |

| Depth: 33 | |

| Weight (g) :390 |

For brevity, I have not included what a recordering device record might look like. Presumably, it would be have similar characteristics to a microphone record.

Bibliography

- Alpaslan-Roodenberg, Anthony, Babiker, Bánffy, Booth, Capone, Deshpande-Mukherjee, Eisenmann, Fehren-Schmitz, Frachetti, Fujita, Frieman, Fu, Gibbon, Haak, Hajdinjak, Hofmann, Holguin, Inomata, Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Keegan, Kelso, Krause, Kumaresan, Kusimba, Kusimba, Lalueza-Fox, Llamas, MacEachern, Mallick, Matsumura, Morales-Arce, Matuzeviciute, Mushrif-Tripathy, Nakatsuka, Nores, Ogola, Okumura, Patterson, Pinhasi, Prasad, Prendergast, Punzo, Reich, Sawafuji, Sawchuk, Schiffels, Sedig, Shnaider, Sirak, Skoglund, Slon, Snow, Soressi, Spriggs, Stockhammer, Szécsényi-Nagy, Thangaraj, Tiesler, Tobler, Wang, Warinner, Yasawardene & Zahir (2021)

- Alpaslan-Roodenberg, S., Anthony, D., Babiker, H., Bánffy, E., Booth, T., Capone, P., Deshpande-Mukherjee, A., Eisenmann, S., Fehren-Schmitz, L., Frachetti, M., Fujita, R., Frieman, C., Fu, Q., Gibbon, V., Haak, W., Hajdinjak, M., Hofmann, K., Holguin, B., Inomata, T., Kanzawa-Kiriyama, H., Keegan, W., Kelso, J., Krause, J., Kumaresan, G., Kusimba, C., Kusimba, S., Lalueza-Fox, C., Llamas, B., MacEachern, S., Mallick, S., Matsumura, H., Morales-Arce, A., Matuzeviciute, G., Mushrif-Tripathy, V., Nakatsuka, N., Nores, R., Ogola, C., Okumura, M., Patterson, N., Pinhasi, R., Prasad, S., Prendergast, M., Punzo, J., Reich, D., Sawafuji, R., Sawchuk, E., Schiffels, S., Sedig, J., Shnaider, S., Sirak, K., Skoglund, P., Slon, V., Snow, M., Soressi, M., Spriggs, M., Stockhammer, P., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Thangaraj, K., Tiesler, V., Tobler, R., Wang, C., Warinner, C., Yasawardene, S. & Zahir, M. (2021). Ethics of DNA research on human remains: five globally applicable guidelines. Nature, 599(7883). 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04008-x

- Baskauf & Webb (2016)

- Baskauf, S. & Webb, C. (2016). Darwin-SW: Darwin Core-based terms for expressing biodiversity data as RDF. Semantic Web, 7(6). 629–643. https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-150203

- Baskauf, Wieczorek, Deck & Webb (2016)

- Baskauf, S., Wieczorek, J., Deck, J. & Webb, C. (2016). Lessons learned from adapting the Darwin Core vocabulary standard for use in RDF. In Hitzler, P. & Janowicz, K. (Eds.), Semantic Web, 7(6). 617–627. https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-150199

- Bird & Simons (2004)

- Bird, S. & Simons, G. (2004). Building an Open Language Archives Community on the DC Foundation. In Hillmann, D. & Westbrooks, E. (Eds.), Metadata in practice.. American Library Association.

- Cox (2021)

- Cox, S. (2021). Why is dctype:PhysicalObject ‘inanimate’?. Retrieved from https://github.com/dcmi/usage/issues/101

- Thomas (2015)

- Thomas, M. (2015). Bones as a Bridge between Worlds: Responding with Ceremony to the Repatriation of Aboriginal Human Remains from the United States to Australia. In Darian-Smith, K. & Edmonds, P. (Eds.), Conciliation on colonial frontiers: conflict, performance, and commemoration in Australia and the Pacific Rim.. Routledge.

- Endresen & Knüpffer (2012)

- Endresen, D. & Knüpffer, H. (2012). The Darwin Core Extension for Genebanks Opens up New Opportunities for Sharing Genebank Datasets. Biodiversity Informatics, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.17161/bi.v8i1.4095

- Guenther (1999)

- Guenther, R. (1999). Dublin Core Resource Types list. Library of Congress. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/marc/dc/typelist-19991118.html

- Ostermaier & Bolliger (2008)

- Ostermaier, B. & Bolliger, P. (2008). Creating Location-Based Services by Utilising a Web of Places. IEEE Computer Society. https://doi.org/10.1109/SAINT.2008.49

- Ousley, Billeck & Hollinger (2005)

- Ousley, S., Billeck, W. & Hollinger, R. (2005). Federal Repatriation Legislation and the Role of Physical Anthropology in Repatriation. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 128(S41). 2–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20354

- Paterson III (2022)

- Paterson III, H. (2022). DCMIType PhysicalObject. Retrieved from https://github.com/dcmi/usage/issues/117

- Paterson III (2022)

- Paterson III, H. (2022). An OLAC Perspective on Services: The Forgotten Language Resources. Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. Retrieved from https://hughandbecky.us/Hugh-CV/talk/2022-services-the-forgotten-language-resources/DC_2022_Conference_Paper_Paterson_Revisions_pre-print.pdf

- Paterson III (2022)

- Paterson III, H. (2022). Where Have All the Collections Gone?: Analysis of OLAC Data Contributors’ use of DCMIType ‘Collection’. Society of American Archivists. Retrieved from https://www2.archivists.org/am2021/research-forum-2021/agenda#peer

- Watson (2003)

- Watson, N. (2003). The Repatriation of Indigenous Remains in the United States of America and Australia: A Comparative Analysis. Australian Indigenous Law Reporter, 8(1). 33–44. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26479533

-

see also: http://purl.org/dc/terms/coverage ↩︎

Categories: