Abstract

The work of many linguists, grant funded projects, and journals which focus on regional or areal linguists rather than “state-of-the-art” discussions are in danger of going unnoticed, including much of the fantastic work done at LLACAN. One method to mitigate the hidden nature of these resources is to create indexes which comply with the Open Language Archives Community standard. The Open Language Archive Community (OLAC, Simons & Bird 2003) metadata standards are foundational in sharing the existence of language materials. OLAC was designed to promote resource discoverability across institutional archives and was built with professional data transmission standards used in library sciences. However, anyone can submit indexes to OLAC—including indexes of personal collections. Indexes are fairly straightforward to create; they deliver descriptions and identifiers pointing out where to find the resources. All that is needed is a published feed, essentially a string of XML data, that points OLAC to the URL where the index is located.

In 2012 at the Satellite Workshop for Sociolinguistic Archive Preparation (LSA, Portland) it was expressed that many individual scholars, who might have data, do not have the desire to formally archive their data based on institutional policies. They do not want to openly share the data itself, but they do want people to know it exists. Even if scholars do archive in their institutional repositories (such as HAL), broad-scope search engines (GoogleScholar) may choose to ignore these resources (Arlitsch and O’Brien 2012). Academically-oriented social networks (academia.edu and researchgate.net) attempt to find a business opportunity in this discoverability gap (Ovadia 2014; Niyazov, et al. 2016). Social network solutions and institutional repositories fail to aggregate resources based on formal ontologies which are meaningful for linguists. As a result, the work of many retired and late-career linguists is being “lost” to convenient and “required” platforms. Convenience also drives some early-career linguists to use costless-deposit archives (Zenodo, Figshare, and OSF) without considering discoverability. OLAC lists 390,035 items across participating archives (as of July 2020); Glottolog lists references for 338,158 items as of version 4.2.1. However, OLAC numbers do not necessarily reflect the actual language resources in archives, and Glottolog numbers reflect more publications than archival materials. Several archives only sporadically updated their metadata feed to OLAC. For instance, the SIL Language and Culture Archives report that it has 46,000 items via its website (August 2020). However, only 30,177 are visible in OLAC with submission dates ranging from 2013 through May 2021.

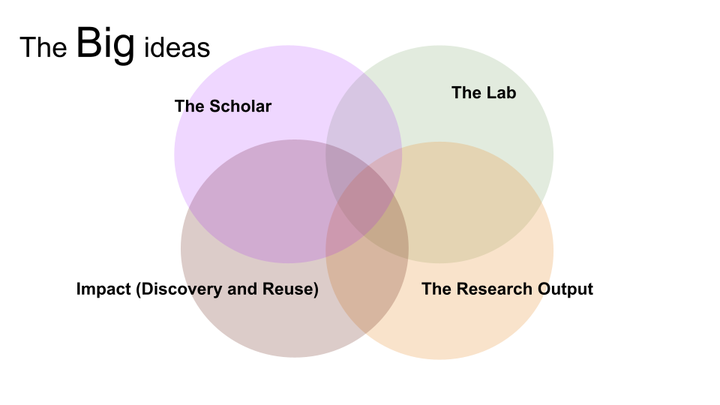

Even if language materials are deposited in an OLAC participating archive, they may not be discoverable through OLAC. This leaves it up to the individual or their lab to advertise the existence of their works. By my calculations, the number of linguistic descriptions grows by approximately 15,000 items per year. Many of these items never find their way into OLAC or Glottolog — or more specifically language research related indexers. I propose that the best way for researchers to optimize their social profile — advertising their experience and academic output — is to archive their content within institutional repositories but self-host a CV-oriented website, pushing metadata to aggregators.

Using open source technologies following strategies outlined by Utomo & Falahah (2020) I use Hugo and the WowChemy theme to demonstrate how a researcher or lab can achieve these goals without the use of traditional server technologies. I do this with a modified RSS feed that compiles metadata and produces an OLAC compliant data feed, the researcher can then advertise language descriptions directly through OLAC.

Bibliography

- Arlitsch & O'Brien (2012)

- Arlitsch, K. & O'Brien, P. (2012). Invisible institutional repositories: Addressing the low indexing ratios of IRs in Google Scholar. Library Hi Tech, 30(1). 60–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378831211213210

- Niyazov, Vogel, Price, Lund, Judd, Akil, Mortonson, Schwartzman & Shron (2016)

- Niyazov, Y., Vogel, C., Price, R., Lund, B., Judd, D., Akil, A., Mortonson, M., Schwartzman, J. & Shron, M. (2016). Open Access Meets Discoverability: Citations to Articles Posted to Academia.edu. In Dorta-González, P. (Eds.), PLOS ONE, 11(2). e0148257. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148257

- Ovadia (2014)

- Ovadia, S. (2014). ResearchGate and Academia.edu: Academic Social Networks. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 33(3). 165–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2014.934093

- Simons & Bird (2003)

- Simons, G. & Bird, S. (2003). The Open Language Archives Community: An Infrastructure for Distributed Archiving of Language Resources. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 18(2). 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/18.2.117

- Utomo & (2020)

- Utomo, P. & (2020). Building Serverless Website on GitHub Pages. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 879. 012077. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/879/1/012077

Categories:

Content Mediums: